Virtual

reality gets easier

By

Kimberly Patch,

Technology Research NewsA common complaint about software is it is not easy to use. If it is difficult to design an intuitive word processing program, however, it's even harder to find obvious ways for people to control virtual environments.

In the dozen or so years since the graphical user interface (GUI) caught on, we have come to expect standard widgets like buttons and menus, and consistent ways of interacting with the interface, like dragging and dropping.

So even if it is difficult to find where the programmer has stashed the "options" menu, it's a matter of looking under all the menu items at the top of a window rather than wondering where to begin.

Although virtual reality software is not brand-new, the tools that allow people to develop virtual environments do not provide standard widgets and interaction techniques; this is largely because virtual reality programs immerse users in environments that don't all look alike, said James Willans, a research student at the University of York in England. "Virtual environments [lack] consistency between applications because they're developed to simulate real world interfaces or to support highly specialized tasks," he said.

This makes it difficult to develop standard ways of getting around them, he said.

York University researchers have developed software that separates the process of designing interaction techniques from the process of building a specific virtual environment, making it easier for developers to design realistic interaction techniques and try them out on users, according to Willans.

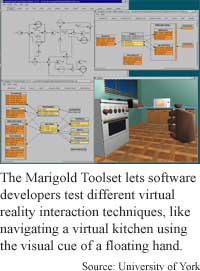

The Marigold toolset is an attempt to find easier ways to design virtual environments like flight simulators where it is important to make the interaction between the user and the environment as realistic as possible.

Making a virtual environment involves using a three-dimensional modeler to build objects that will reside in the virtual world, then using a virtual environment toolkit to define the parts of that world that will be interactive. Although building objects is fairly intuitive, designing how users will interact with the objects is much more complicated.

No single interaction technique is suitable for all applications, even for abilities as basic as the way a user is allowed to move around the environment, said Willans. For instance a user could "move quickly from one location to another or [be] constrained to moving a certain speed, or interact in such a manner that they can tell from the position of their physical body the position and orientation of the virtual world," he said.

This is where the trouble usually starts, according to Willans. Just like GUI development tools, virtual environment toolkits provide predefined interaction techniques, but the virtual environment tools do not work well across all the environments developers may want to create. This often results in developers choosing standard interaction techniques "without considering the precise nature of the application they're supporting," said Willans. The result is an environment that may look very good, but won't be used if it is difficult to navigate, he said.

Even when developers try to consider interaction in light of the environment they're building, the tools don't offer much support, he said. "The abstractions used in virtual environment toolkits make defining the interaction complex."

The toolkits use simple geometric objects to represent how the environment responds to a user, said Willans. Visually, "these bear little little or no correspondence to our real-world understanding," he said.

The researchers attempted to solve these problems by giving developers a way to visually specify the techniques they're designing.

Marigold uses a flowchart tool developed by researchers at York University and Rutherford Appleton Laboratories that diagrams interaction techniques. Marigold then builds a prototype from the diagram so the developer can try out the interaction techniques in context, according to Willans.

This allows the developer to find better ways for users to interact with a specific environment. This transition between the design and a prototype of the design "can be used to evaluate the suitability of the design with users," said Willans.

The tool automatically checks the design to make certain that it will support specific requirements, Willans said. "For instance, whether... a virtual door cannot be opened when locked." It also checks to make sure users can understand from what they see on the screen how their interactions will be interpreted, he said.

The work is "in essence trying to create a better specification language," said Scott Hudson, an associate professor of human-computer interaction at Carnegie Mellon University. The work is related to earlier work on GUI development tools that use specifications, but the researchers have applied the approach to virtual environments, said Hudson. In doing so the researchers have made some "significant advances," adapting them to accommodate the more fluid interactions of virtual environments, he said.

Usability problems are a serious issue because the keyboard and mouse are often not viable in a virtual environment, said Scot Thrane Refsland, director of research and Development at the center for Design and Visualization at the University of California at Berkeley.

"The challenge is to create new ways of interaction that enable the user to interact effectively. As is the case with many industries, sometimes the tools aren't developed by the people who use them, creating bad interfaces that aren't effective," he said. The York University tool addresses the problem by probing deeper into the issues of modeling and verifying interaction techniques, he added.

Developing interfaces for virtual environments is a difficult problem not only due to the lack of viable standardized interaction techniques, but also because human behavior is so very complicated, said Hudson. Because of this, "we have little practically applicable theory that can help us design usable systems from base principles" he said. The usual fall-back is a cycle of testing with users and redesigning, which makes it especially important to be able to test interfaces during the design process, he said.

Willans research colleague is Michael Harrison of the University of York in England. They published the research in the August 1, 2001 issue of the International Journal of Human Computer Studies. The research was funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Timeline: Now

Funding: Government

TRN Categories: Human-Computer Interaction

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "A Toolset Supported Approach for Designing Testing Virtual Environment Interaction Techniques," International Journal of Human Computer Studies, August 1, 2001; Marigold Website:

Advertisements:

November 7, 2001

Page One

Hubs key to Net viruses

Electrified water spins gold into wire

Virtual reality gets easier

Laser emits linked photons

Dye brightens micromachines

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.