VR

tool aims high

By

Kimberly Patch,

Technology Research NewsWe've known for a very long time that when it comes to learning some things, there's no substitute for experience. Researchers working to make virtual environments stand in for the real thing have spent the past few decades learning that actual experience is very hard to mimic.

A large group of researchers from the University of Southern California is working on a virtual environment that coordinates a raft of technologies -- and some Hollywood craft -- to take a step toward this end.

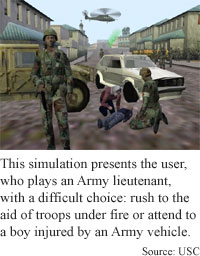

The project, funded by the U.S. Army, simulates a war-torn village where an officer on a peacekeeping mission has to make a difficult choice between joining a unit that is under attack and slowing down to get medical help for a boy hurt by an Army truck.

The technology could ultimately be used to represent any type of environment, allowing people to travel to and learn by experience in places and times where they couldn't ordinarily go, said Jeff Rickel, a project leader at the University of Southern California's Information Sciences Institute. "If you want to teach kids about ancient Greece... there's probably no substitute for just putting them in ancient Greece, [and] letting them experience the sights and the sounds... and interact with the people," he said.

Making an environment that includes believable human characters, however, is a difficult task involving a lot of interconnecting technology.

On the output side -- technologies that allow a human to experience the environment -- the researchers used 3-D computer modeling to project life-size figures on an 8- by 130-foot curved screen, a 12-speaker surround sound system, software models of emotion, a flexible storyline, speech generation software, and computer agent software that allows characters to gesture as they speak.

On the input side -- technologies that allow the computer-generated characters to react to the human using the system -- the researchers are tackling several speech recognition challenges and are using computer vision to understand pointing gestures.

The researchers also used Hollywood scriptwriters to make the scenario emotionally convincing. "You get engrossed in [a movie] because the writers and directors have done such a nice job of making it compelling and gripping. We want to create stories that are so emotionally gripping that people forget their training situation and react the way they would as if they were really in the field," Rickel said.

The difficult part is coordinating everything, because the various technologies have many interdependencies that the individual components don't address, said Rickel. For example, adding a model of emotion to a character means coordinating it with the character's natural language understanding, speech synthesis and decision-making software, he said.

"One of the challenges is to assemble this team of experts in all these different areas... and not just plug the stuff together, but have them hash out how these modules actually work together to create one virtual human," said Rickel.

The characters were built from intelligent agent software developed in an earlier project. The original agent was a humanlike knowledge base that was able to show the user around an environment, point to things, and explain them.

The project's aim is to make more realistic characters that have emotions, finely tuned gestures, an understanding of users' gestures, an ability to recognize words in noisy environments and eventually an ability to interpret word meanings.

In their pursuit of more realistic characters, the researchers also subtracted something from the original agent: its omniscient knowledge of its environment, like how much gas is in a certain tank. Now the characters have to look at gauges in order to gain that knowledge, as a human would.

In the army scenario, the researchers are trying to create a realistically stressful environment, said Rickel "One of the ways we do that is to create characters in the story that are getting emotional and... affecting the user through these emotions," he said.

In the simulation, the lieutenant played by the user is tugged in two different directions by emotional displays from various characters. Radio calls from the user's unit downtown get increasingly angry, "saying 'where are you, we're taking fire, we need your help, you're letting us down'," Rickel said. At the same time, right in front of the user is an injured boy and the boy's mother, who gets increasingly emotional if the user starts to send his troops to help the unit downtown.

To display these emotions, the Army characters on the radio and the mother character are dynamically reacting to the user's actions.

The models of emotion have drawn heavily from psychology literature, and in particular have been influenced by "models of how emotions come out of plans and goals that we have... and when somebody takes action that thwarts our plans and goals... we may get angry," he said.

The emotion software recognizes that the unit's moving out may conflict with the mother's goals, displays the appropriate emotions, and coordinates the effect those emotions have with the character's further actions.

In order to communicate with the user realistically, the characters must be able to convey emotion with their voices. This is something the researchers are still working on. "One of the biggest challenges that we face is emotionally expressive speech," said Rickel.

"When you have the character like the mother who is supposed to be getting very emotional [and] whose emotions are supposed to help draw the user in... if she sounds robotic like most speech synthesizers these days, it's going to completely destroy the effect," said Rickel.

The researchers are using recordings of a voice actor for the Army project, but they're working on being able to do the same thing using speech synthesis, which will allow for a more flexible storyline. "The research we're doing in voice synthesis is to study acoustic patterns that you see in emotionally expressive speech and try to reproduce that on-the-fly in a character like the mother so the we don't have to script her lines ahead of time," he said.

To do this, the researchers are tapping a relatively old technique called concatenative speech. "It's basically splicing together bits of text from lots of speech samples, in contrast to the other main approach, which is [building speech from] sounds for individual phonemes," Rickel said. With a large enough database, a speech synthesizer can theoretically pull out enough pieces to, for instance, allow a sergeant to convincingly bark an order, he said.

Humans use both speech and gestures to communicate. The researchers are working on incorporating gestures into the characters' communications to make them more realistic. "We're using... movements of the hands that accompany speech [and] probably don't have any meaning by themselves but... serve to emphasize words and convey the impact of those words," Rickel said.

The researchers are also using computer vision technology to give the characters the ability to react to the user's gestures. The challenge in gestural understanding is to allow the character to recognize that the total message is a combination of speech and gesture when the user is, for instance, pointing at an object and saying 'Go get that,' Rickel said.

It's also important that the characters understand the user by recognizing the words the user says even in noisy situations, recognizing the emotion attached to those words and, eventually, being able to discern the meaning of those words. These tasks are beyond the capabilities of today's standard dictation software, which simply recognizes words, and only when conditions are good.

"One challenge is to actually recognize the emotional content of the message... and still recognize the words despite the fact that the person is emotional," Rickel said.

The system's sound environment is also a difficult challenge for the speech recognizer. The 12-speaker surround sound system brings the user 3600 watts of power through 64 channels. For comparison, the 20,000-seat Hollywood bowl uses a 3500-watt speaker system. "If you've got helicopters buzzing over[head] and an angry crowd yelling at the guy and a distraught mother screaming for help for her boy, then it's a pretty noisy environment," said Rickel. This is very different from what today's speech recognizer's can generally handle, he said. "So one of the challenges for speech recognition is how do you -- like a person -- pick out the speech that this person is saying in the midst of all this other noise," he said.

A future challenge is natural language understanding, which will allow the characters to not only recognize words, but interpret their meaning. This would allow for a much more flexible story. Currently, the human participants have to stay close to a script.

The researchers are also working toward making the characters more automated by giving them a wider range of movements. Currently the characters' motions are generated by capturing the motion of real humans. Motion capture is realistic, but, like using voice actors to script emotional speech, limits the storyline's flexibility, said Rickel. "We're looking at how we can generate animations on-the-fly that retain the realistic look of motion capture [but] give you more flexibility," he said.

Pulling off convincing characters for any length of time or for scenarios that aren't closely scripted is an incredibly difficult artificial intelligence problem that's not likely to be solved anytime soon, said Terry Winograd, a professor of computer science at Stanford University.

The question to ask about the Army demo research is whether "it's going to build scientific knowledge which in the future will let us build realistic things," said Winograd, adding "that's a hard question to resolve. "

It's not clear whether demos like the Army project really delve into the hard intelligence problems that humans solve instinctively, he said. "There are some mechanisms that we just have no understanding of, yet they go on inside your brain, inside your body, inside your hormones. [It is] relatively easy to observe the behaviors of people who are having emotions and... mimic these behaviors in a simple pattern-driven kind of way. [But] it's not going to be consistently like a person... it'll only be when you happen to hit the right pieces of pattern," he said.

Rickel's research colleagues were William Swartout, Randy Hill, John Gratch, W. Lewis Johnson, Chris Kyriakakis, Catherine LaBore, Richard Lindheim, Stacey Marsella, David Miraglia, Ben Moore, Jackie Morie, Marcus Thiébaux, Larry Tuch, Richard Whitney and Jay Douglas of the University of Southern California. They are scheduled to present their research at the Agents 2001 conference in Montreal, May 28-June 1, 2001. The research was funded by the Army Research Office.

Timeline: Now

Funding: Government

TRN Categories: Human-Computer Interaction; Artificial Intelligence

Story Type: News

Related Elements: Technical paper, "Toward the Holodeck: Integrating Graphics, Sound, Character and Story," scheduled for presentation at the Agents 2001 conference in Montreal, May 28-June 1, 2001. Technical paper, "Steve Goes to Bosnia: Towards a New Generation of Virtual Humans for Interactive Experiences," presented at the AAAI Spring Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Entertainment in at Stanford University, March 26-28, 2001.

Advertisements:

May 30, 2001

Page One

VR tool aims high

Bulk nanotubes make clean crystals

Engine fires up electrical devices

Microscopic stamps make nanotech devices

How metallic are metal nanotubes?

News:

Research News Roundup

Research Watch blog

Features:

View from the High Ground Q&A

How It Works

RSS Feeds:

News

Ad links:

Buy an ad link

| Advertisements:

|

|

Ad links: Clear History

Buy an ad link

|

TRN

Newswire and Headline Feeds for Web sites

|

© Copyright Technology Research News, LLC 2000-2006. All rights reserved.